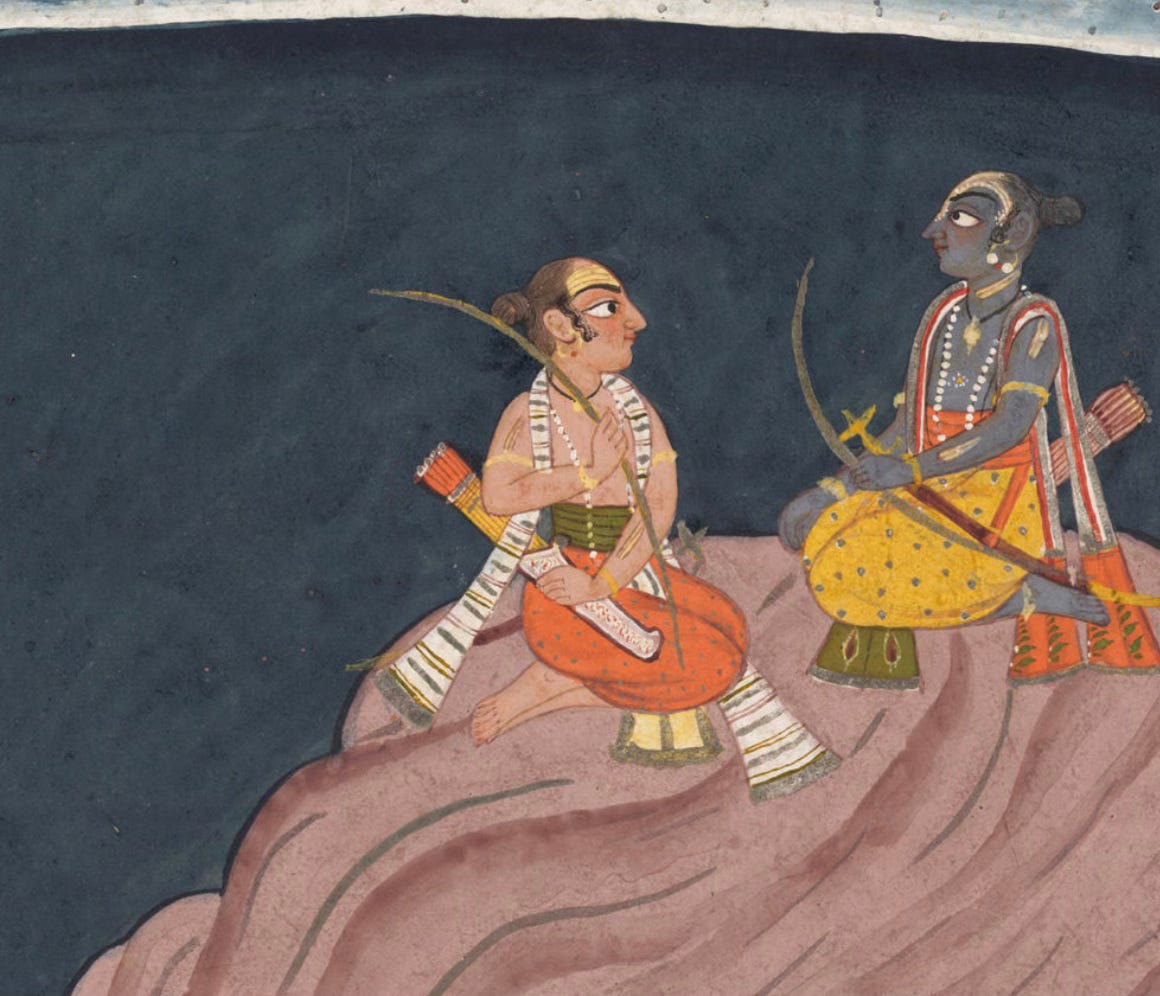

The (Real) Rāmāyana

It may come as a shock, but many of the most celebrated episodes we associate with the Ramayana are nowhere to be found in the ancient verses of Vālmiki’s original work.

Every Indian has heard the story of the Rāmāyana – and chances are, most of us have read or heard at least a couple of versions of it. Over the generations, so many episodes have become part of our collective memory. But as I discovered while working on the draft of my manuscript on the Vālmiki Rāmāyana, a lot of those well-known moments don’t actually appear in the original work by Vālmiki. Many of them were added later by poets and storytellers, who brought their own creative touch – sometimes even enriching the epic without straying from the deeper vision of Vālmiki. Here are a few such examples that stood out to me.

The Story of Ahalyā

We’ve all heard the story of Sage Gautama cursing his wife Ahalyā to turn into stone after she had an affair with Indra. But when I went through the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, I found something quite different. The original doesn’t say anything about her turning into stone. Instead, she’s cursed to become invisible to all beings, surviving only on air, and basically cut off from the world – until Rāma comes along and redeems her. (Bāla Kānda, Sarga 48, Verses 18–19)

The whole “turned into stone” idea actually comes much later. The earliest reference to it shows up in Kālidāsa’s Raghuvaṃśa, where he says Ahalyā was turned into a rock and returned to her human form when touched by Rāma’s feet (Raghuvaṃśa, Canto 10, Verse 31). It’s a beautiful metaphor if you think about it – being like a stone suggests she had completely withdrawn from the world, perhaps as part of a long inner journey.

Popular retellings also add that she was brought back to life when Rāma stepped on the stone, or when the dust from his feet touched it. That version really emphasises Rāma’s divinity – how even the dust of his feet can awaken someone who’s been “petrified” for years. But in the original, it’s actually Rāma and Lakshmana who fall at her feet as a mark of respect, and Ahalyā is described as looking like a radiant flame hidden under smoke. (Bāla Kānda, Sarga 48, Verse 33)

And what’s really interesting is this: all versions agree that Rāma meets Ahalyā before marrying Sitā. Think of it this way – the young prince helps repair a broken marriage before stepping into his own. This little detail says a lot.

Sita Svayamvara

In a lot of popular retellings, we hear that Rāma showed up at Sitā’s svayamvara along with a bunch of other suitors. Some even say that Rāvana himself came to compete – that he tried to lift Shiva’s mighty bow, failed miserably, and got laughed at by Sitā and her friends. That public humiliation supposedly becomes one of the reasons he decides to abduct her later on.

But when you read Vālmiki’s Rāmāyana, it’s a different story altogether. There’s no grand svayamvara ceremony, no parade of kings, and definitely no mention of Rāvana trying (and failing) to lift the bow. What actually happens is that Rāma and Lakshmana go to King Janaka’s court with Sage Vishvāmitra, who casually mentions Shiva’s bow and sparks Rāma’s interest. Rāma walks up to it, picks it up, strings it with ease, and the bow snaps in his hands (Bāla kānda, Sarga 67, Verses 10–15). That’s it. No drama, no competition. Janaka, stunned by what just happened, offers Sitā’s hand in marriage right then and there.

Also, there’s no episode in the original where Sitā lifts the bow as a child while playing ball with her friends – that’s another later addition.

Interestingly, the bow itself has quite a backstory. According to the epic, Lord Shiva had once used it during Daksha’s yagna—the same one where Pārvati immolated herself after being insulted by her father (Bāla Kānda, Sarga 66, Verse 10).

Shurpanakhā

In some versions of the Rāmāyana, we’re told that Shurpanakhā was so smitten by Rāma’s looks that she came to him disguised as a beautiful woman, hoping to woo him. Sounds familiar, right? But when you actually look at the Vālmiki Rāmāyana, that’s not how it happens at all. She approaches him in her original, terrifying rākshasi form—no illusions, no beauty spell. (Aranya Kānda, Sarga 17, Verses 17–19)

It’s the folk and later versions that seem to have added the idea that she changed her form. Since rākshasas are believed to be shape-shifters, storytellers probably just ran with that and imagined her coming as a lovely woman. And honestly, it works – it adds this extra layer to her character, making her seem more cunning and deceptive. It also fits with the idea that rākshasas, who are driven purely by desire and obsessed with the physical, use outer appearances to manipulate and seduce.

So, in a way, that creative liberty gives us a sharper picture of who Shurpanakhā is – not just a rākshasi, but someone symbolic of illusion and material craving.

Lakshmana Rekhā

You’ve definitely heard of the famous lakshmana-rekhā – that protective line Lakshmana supposedly draws around the hut before he leaves to look for Rāma. It’s one of those iconic moments in the Rāmāyana that everyone seems to remember. But interestingly, when you study the Vālmiki Rāmāyana, there’s no mention of it at all. No line, no instruction, nothing. (Araṇya Kāṇḍa, Sarga 45–46). And it’s not just Vālmiki – even other classical Sanskrit versions don’t mention the line either.

So where did it come from? Most likely from later folk and regional versions, where storytellers added it in as a symbolic gesture – and what a powerful addition it is. That one line says so much about Lakshmana’s character. It turns a simple act into a declaration of devotion. The idea that a mere line drawn by him could stop Rāvana – the king of Lankā, conqueror of the three worlds – adds a symbolic weight to Lakshmana’s loyalty and strength. It suggests that it’s not brute force, but dharma and integrity that hold the greatest power in this world.

Metaphorically, the lakshmana-rekhā can be seen as the boundary between duty and desire, between caution and temptation. Sitā crossing the line isn’t just a plot point – it becomes a symbol of crossing the threshold of trust, of stepping outside the space protected by love, care, and dharma. The line could also represent the fragile boundaries we set in our own lives – between right and wrong, spiritual and material, discipline and impulse. Lakshmana’s line, then, becomes more than just a physical barrier – it’s a moral one – it is the line of dharma.

And here’s something I love about this addition: even though it’s not “original,” it feels spiritually authentic. It highlights Lakshmana’s role not just as a loyal brother, but as a guardian of values, of sacred space. His devotion is so intense that even a symbolic gesture – an imaginary line – takes on divine power. Whether or not he actually drew it, the lakshmana-rekhā captures the essence of who Lakshmana is.

Sitā’s Abduction

So, here’s a surprising one: in Vālmiki’s Rāmāyana, Rāvana doesn’t abduct Sitā in the legendary pushpaka-vimāna. Instead, he carries her away in a magical chariot pulled by donkeys. Yep, you read that right – donkeys! (Araṇya Kāṇḍa, Sarga 49, Verses 1–3). Not exactly the glamorous golden chariot we often imagine, right? The abduction scene is raw and disturbing: Rāvana seizes Sitā by her hair with his left hand and her thighs with his right (Verse 14). There’s no shield of divine light, no illusion of distance – it’s visceral, terrifying, and real.

But then, Jatāyu enters the picture. This aging bird-king rises up with heroic defiance – he kills the charioteer, slaughters the donkeys, and smashes the chariot to pieces (Verses 21–29). Rāvana is literally thrown to the ground, still clutching Sitā. It’s a powerful image: not an invincible demon king, but a villain in mid-fall, interrupted in the act of evil by courage and resistance.

Now fast-forward to the regional retellings, and the entire scene transforms. Here, Rāvana abducts Sitā in the pushpaka-vimāna, a divine aircraft worthy of a cosmic drama. And in many of these versions, Sitā’s pativratā – her unwavering devotion to Rāma – is so intense that Rāvana can’t even touch her. Her body radiates fire, a divine force field of chastity. In some stories, he chops off the very piece of earth she stands on and flies away with that instead. That shift isn’t just dramatic – it’s cultural.

These retellings reflect changing ideas of what it means to be a pativratā woman. Over time, Sitā becomes more than just a symbol of loyalty – she becomes untouchable, inviolable, a divine ideal. The narrative begins to place spiritual power in the very concept of female chastity, especially in devotional traditions that elevate the feminine as a goddess-like force. The symbolism of Sitā being born from the Earth and carried away along with it also reinforces her unbreakable link to purity, nature, and dharma.

And then there’s the story of Vedavati – another fascinating addition. In some later versions, it’s said that the real Sitā was never abducted at all. Instead, it was Vedavati in disguise, and the true Sitā was hidden in fire, later returned by Agni during the fire ordeal. Again, this version doesn’t appear in Vālmiki’s text – but it does tie into Uttara Kānda, where we’re told Rāvana once tried to molest Vedavati in the Krita (Satya) Yuga, and she vowed to be reborn to destroy him (Uttara Kānda, Sarga 17, Verses 11–23). Here, Sitā is no longer just a princess caught in a war – she’s an avenger, a cosmic force of justice reborn with a purpose.

And then there are the even more imaginative versions that say Sitā was actually Rāvana’s daughter – rejected at birth and later unknowingly pursued by him. Again, none of this appears in any Sanskrit version of the epic, but it speaks to how regional imaginations played with myth to create layered, sometimes morally complex versions of the tale.

So what does all this tell us?

It shows how each generation and culture reshaped the Rāmāyana to reflect its own values. In Vālmiki’s time, Sitā was a noble woman – dignified, courageous, but also vulnerable. Later traditions transformed her into a divine archetype of purity and spiritual strength. Rāvana shifts from being a powerful but fallible demon-king into a symbol of all that is vile, deceptive, and driven by kāma (lust). And Lakshmana, Jatāyu, even Agni step into symbolic roles – protectors of dharma, of sacred femininity, of divine order.

It’s the beauty of the Rāmāyana tradition. The Rāmāyana is not static. It breathes. And in every breath, it reflects who we are – or who we aspire to be.

Shabri and her Bitten Fruits for Rāma

The story of Shabri is one of the most touching moments in the Rāmāyana, and chances are, you’ve heard the popular version – the one where the old tribal devotee, blind with age, picks berries every day for Rāma, waiting for the moment he might walk into her āshrama. When that moment finally comes, she's so eager to offer him the sweetest berries that she tastes each one before placing it in his hands. Rāma, delighted, eats them joyfully. But Lakshmana? He’s apparently horrified – how could his brother eat something already bitten by someone else? And then Rāma smiles, calms him down, and says that anything offered with pure devotion is more precious than any rule or ritual.

Beautiful, right? It’s one of those stories that shows up in bhakti literature, children’s books, and kathas by orators – and it captures the heart of what bhakti means: love over ritual, sincerity over rules.

But here’s the thing: none of that appears in the Vālmiki Rāmāyana.

In the original, there’s no mention of Shabri being blind, or tasting the berries. No dramatic moment where Rāma schools Lakshmana on the nature of devotion. What actually happens is just as moving in its own way. Rāma and Lakshmana arrive at Shabri’s āshrama, and she welcomes them with deep reverence. She offers them fruits and roots gathered from the forest – not because she tasted them first, but because her entire life has been one long act of waiting, of bhakti. And once she fulfills her life’s purpose – serving Rāma – she performs a yogic self-immolation and ascends to the heavens.

So why did the berry-tasting version become so popular? Because it makes a powerful statement. Over time, as the bhakti movement spread across India, storytellers began reshaping the epic to highlight devotion as the highest virtue – above birth, class, education, or ritual purity. Shabri, being an elderly tribal woman, becomes the perfect symbol of this. She's not a sage, not a scholar, not a royal. She’s a bhakta. And her tasting of the berries becomes a metaphor: she doesn’t know the rituals, but she knows love. And that’s enough. Becoming a bhakta of God is the highest status.

In contrast, the image of Lakshmana being scandalised reflects the conservative, rule-bound mindset that bhakti narratives often challenge. By showing Rāma as lovingly accepting Shabri’s offering, these retellings affirm that God is not bound by social hierarchies or ritual “purity.” Purity of devotion alone is enough.

So even though the berry-tasting episode isn’t “original,” it speaks to a spiritual truth that later generations felt strongly about. It turns Shabri into more than a forest-dwelling devotee – she becomes a symbol of radical inclusion, of unconditional grace.

And that’s the magic of the Rāmāyana. Across centuries, the story has bent and stretched – not to distort the truth, but to express it more deeply. In the hands of saints and storytellers, Shabri’s simple offering becomes a theological statement: God accepts love, not just offerings.

There are plenty of other elements that have become deeply embedded in popular culture, yet surprisingly, they don’t appear in the original Vālmīki Rāmāyana. Some of them are so familiar that we almost assume they’re part of the ancient text – until we actually go back and read it.

For instance, Rāma is never once referred to as “Rāmachandra” in the original epic. That title, though beautiful and poetic, comes from later traditions and devotional literature.

In the Ayodhyā Kānda, we do get the heart-wrenching story of King Dasharatha accidentally killing a young brāhmana boy who was caring for his blind parents. The grieving parents curse Dasharatha, saying he too would die pining for his son. But what’s interesting is that the boy’s name is never mentioned in the original. The name Shravana-Kumāra – so familiar to all of us – comes from later tellings.

The vānaras in Vālmiki’s version are feral, wild, and full of raw energy. They fight with stones, trees, and their own bodies – there’s no mention of maces, swords, or other man-made weapons. But in most popular depictions today, we see Hanumān, Sugriva, and Jāmbavān wielding heavy maces, turning them into warrior-icons rather than primal forces of nature. It’s not wrong – just another layer added over time.

Another common belief is that Lakshmana stayed awake and fasted for all fourteen years in the forest out of devotion to Rāma. While this makes for a powerful devotional image, the original doesn’t say this. It’s one of those beautiful exaggerations that add depth to Lakshmana’s character, even if it isn’t textually supported.

Another major difference shows up in the Uttara Kānda. Here, it’s the general suspicion of the people of Ayodhyā about Sitā’s purity that leads to her exile. But in many popular retellings, this suspicion is pinned on a single character – a washerman – who voices his doubts loudly. This later version adds drama and clarity to the public sentiment, and at the same time, underlines a powerful message: that the king’s actions ripple through society, touching even the most common citizen.

These are just a few glimpses into how the Rāmāyana has been retold, reshaped, and reimagined over the centuries – sometimes staying close to the source text, and at other times, layering it with meanings that reflect the spiritual aspirations, social values, and creative visions of the people who inherited the story. None of these later additions are “wrong”, and who are we to judge them anyway? In fact, many of these later additions are beautiful. They show how alive this story is. The Rāmāyana has never been frozen in time. It has flowed like the Gangā – sometimes clear, sometimes clouded, always moving – with each generation adding its own depth to its waters.

But there is also a unique beauty in returning to the original – a kind of quiet strength in listening to the voice of Vālmiki, the ādi-kavi, the first poet who sang this epic not as mythology, but as itihāsa, “that which truly happened.” His Rāma is not just a god. He is also a man – complex, noble, flawed, compassionate, determined. His Sitā is not just an icon of chastity, but a woman of immense dignity and inner fire. His Lakshmana, Hanumān, Bharata, and even Rāvana are drawn with nuance and humanity. But the greatest part of it all was that Vālmiki was there. He saw Rāma. He saw Sitā. He saw it all.

In my retelling, I hope to bring this original world back into focus – not to argue against the later traditions, but to uncover the layers of wisdom, symbolism, and emotional truth found in the earliest version of the epic. This is a journey through Vālmiki’s words – where the characters breathe with a quiet realism, where divinity and humanity walk hand in hand, and where dharma is not always clear-cut, but something each character must grapple with in their own way.

Through this retelling, we'll explore how a line here or a silence there reshapes the way we understand love, duty, justice, and devotion. We’ll also celebrate the creative spirit of the Bhāratiya storytelling tradition, which has kept this epic alive through villages, temples, performances, and poetry.

There is so much more waiting to be uncovered. So many questions to ask, so many moments to re-look at. If you’ve grown up with the Rāmāyana, this journey might surprise you. If you’re coming to it fresh, I hope it opens something within you.

This is only the beginning.

Stay connected for what’s to come.

Love and Prayers,

Vinay

Intresting.....!! I'm getting to know this all for the first time. Thank You for writing this...🙏🙌

Beautiful. Thank you. 🙏🏽

You are so right about how, although not in the original, the newer re-telling are still just as valuable. Thank you and looking forward to the Publication.